Here are just a few of the geometric shapes (some complex) that serve as powerful tools to understanding abstract problems

Cubes

Cubes are the discrete 3D building block of geometric abstraction. Computationally we can approximate other shapes and functions by discrete sampling or aggregation of tiny cubes. Approximating curves, surfaces, volumes, or hyper volumes can be linked back to Riemann sums in calculus. Basically many tiny rectangular shapes are stacked to mimick other functions and shapes.

Sphere

The sphere is an excellent starting point for simple models or representations. It is useful in modelling the smallest to the largest of force interactions. On a minuscule scale, molecular adhesion naturally wants to form into spheroids. On the scale of galaxies gravitational forces and black hole horizons act along spherical boundaries (in first order models). Bouncing or packing tiny spheres together can model gases, or liquids.

Sections of a sphere are useful for understanding visibility and line of sight between point sources. Intersecting spheroid surfaces form curved lines while intersecting spheroid sections form volumes. Each useful for representing different problems.

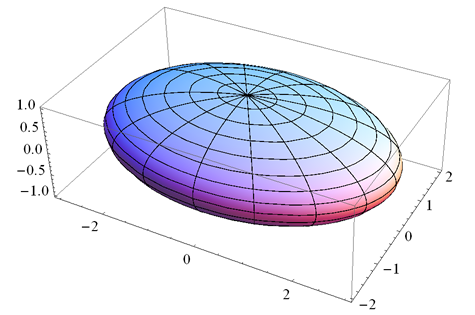

Ellipsoids, when Spheres just aren't enough

Advanced ellipsoid models branch away from sphere like assumptions. Each axis of a smooth surfaced ellipsoid may be different. Geodetic or triaxle models can be used to describe an array of physical or mathematical concepts, here's just a few:

- celestial bodies

- the sigma boundary of gaussian statistical distributions

- rotating solids

Interersecting ellipsoid surfaces and sections can be used for understanding position estimates (again curved lines for surfaces), overlapping sections which form volumes, and/or probability of being within a region (Gaussian).

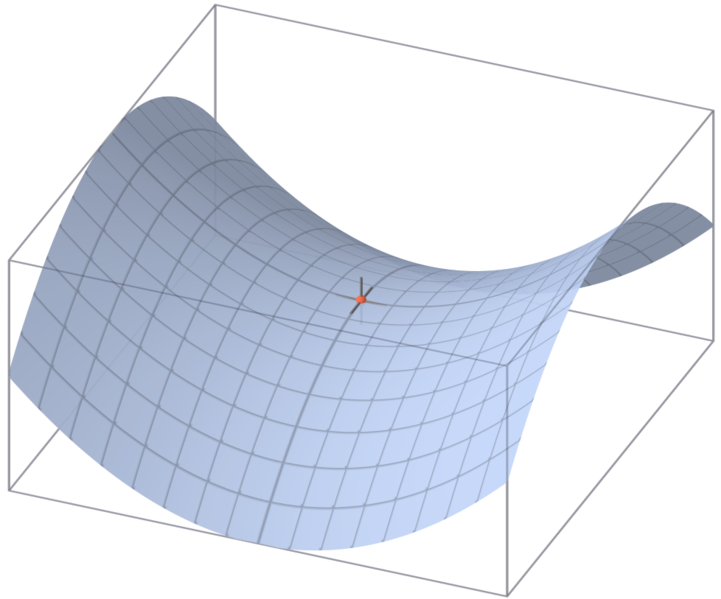

Saddle Shapes

In 2D plots the knee in a curve is often a sweet spot to determine "bang for the buck" or the best utility per cost. This is related to Pareto Principleor 80% performance for 20% cost.

There are saddle shape surface functions which help us understand the maximum of one parabolic function as it meets the minimum of another parabolic function. These are the beloved "knees" in 3 or more dimensions which many parametric functions are notorious for. We strive to develop systems which adapt to changing systems (the saddle moves) and maintain near optimal tradeoffs.

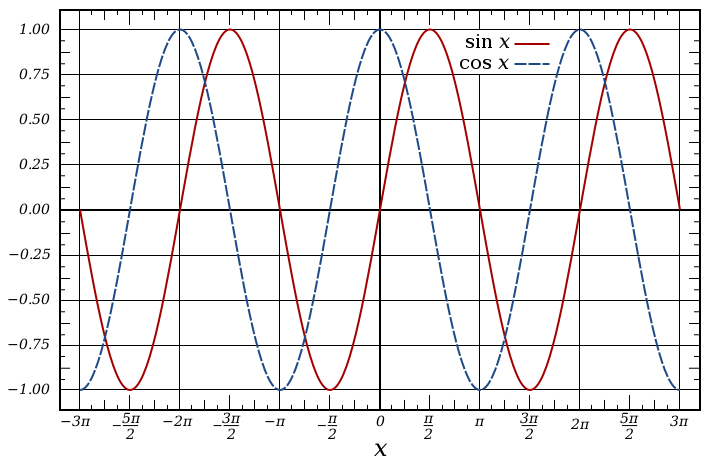

Sinusoids

While not a geometric shape, I couldn't leave out the powerful utility of the sinusoid as a tool in representing abstract concepts. From electro-magnetc waves of light to surface waves of water we witness wave geometries in nature of all forms and sizes. Quantum waves and shock waves from explosions are all sinusoid variations. Often we combine the sinusoid with a exponential weighting, serving as an envelope (laser beams spread out, shock waves diminish).

A popular application such as Fourier transforms (decomposing a signal into a sum of sinusoids) is analogous to using cubes to estimate arbitrary shapes. One of the desirable features of Fourier transforms is that convolutions (computationally expensive) are simple products in frequency domain.

One of the more "far out" realizations of sinusoids is quantum computing, of which I have only the simplest of understandings. The potential of searching many possible outcomes simultaneously is the holy grail of parallel processing. The trick is adding quantum bits and finding the right answer when you finish processing.

Related articles by Zemanta

- Code-Breaking Quantum Algorithm On a Silicon Chip (science.slashdot.org)

- Scientists Make Breakthrough With First Programmable Quantum Processor [Quantum Computer] (gizmodo.com)