How the Hell do Big Infrastructure Projects Succeed?

This question and brief study was prompted by several conversations I engaged in yesterday. Andy Swan has been working towards getting to the root of contrasting social versus capitalistic systems of motivation. At the same time another asynchronous discussion happened on AVC, "Would AT&T or Comcast have created Google?". Fred was thinking out loud about the assumptions for his position on Net Neutrality. Finally I wrapped up the day with a good chat with coworker Eric Jansen. We talked briefly about the history of the US government support of large scale infrastructure projects. The specific relationship between the US Government (ultimate in crowd sourcing) and private business execution is what I'll review.

First off, I spent some time basking in the glow of Net knowledge. I read about the history of the US railroads, the Panama Canal, the Hoover Dam, and the Internet and it's infastructure (random sample).

Each of these monumental infrastructure projects was initiated by the government either by direct contracts, low interest loans, or research grants. The capital to cover the costs of these mega projects and organizational ability were beyond the resources of a single company.

These huge infrastructure projects all share some common driving features. There was a great perceived need, that would benefit the future in monumental efficiency boosts. No set of private companies was willing to take the risk of implementing a solution, the challenges were just too great. The US Government served as a risk proxy in these cases, essential eating the costs of the design and construction but relegating ownership and upkeep of these resources to external organizations (with some federal oversight).

I can imagine an argument in favor of hands off capitalism. It would require independent businesses to fulfill the need of the populace. The challenge is getting private competing entities to come together and collaboratively design and execute a project of enormous scale. In addition, working out agreed upon standards is no small debate. This would limit the long term restrictions and oversight that a connection to federal funding creates, but careful observance of a competitive environment would be needed.

Contrary to the capitalist argument, history has shown that federal crowd sourced funding and management was necessary to initiate all these projects.

I envision an alternative future method for mega scale projects. It will be founded on global crowd sourced funding. The execution of a huge infrastructure project requires cooperation among many corporate leaders, working in unison. A dedicated nonprofit of diverse people would be needed to oversee and decide on design and execution options. The long term benefits of such an initiative are immeasurable. The entirety of humanity working together towards a single outcome would be a miracle in of itself. Just imagine what a few trillion dollars investment could do to global infrastructure (transport, communication, trade). It's time we all invest in the wealth of the world, by long term planning. Short sighted thinking has left those who inherit our imagination with a grim future.

Some of the Gritty Details

I'll wrap up with the references, and quoted sections that helped me "catch up" on the history of these large scale projects. My reading focus was on the development success, efficiency and motivation of those executing the construction projects. A grim pattern of many lives lost accompanied each mega project, except for the Internet.

US History of Railroads and modern US rail transport. This quite captures the essential relationship between private and government control of railway developmet:

Industrialists such as Cornelius Vanderbilt and Jay Gould became wealthy through railroad ownerships, as large railroad companies such as the Grand Trunk Railway and the Southern Pacific Transportation Company spanned several states. In response to monopolistic practices and other excesses of some railroads and their owners, Congress created the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) in 1887. The ICC indirectly controlled the business activities of the railroads through issuance of extensive regulations. Congress also enacted antitrust legislation to prevent railroad monopolies, beginning with the Sherman Antitrust Act in 1890. The United States Railroad Administration temporarily took over management of railroads during World War I, which led to standardization of equipment and reductions of duplicative passenger services.

Panama Canal. The first attempt at constructing a canal across the isthmus (Panama) ended with tragic failure (over 20,000 workers lost their lives due primarily to disease). After some political maneuvering by Cromwell the US began tackling the construction in 1905.

Chief Engineer (1905–1907), John Frank Stevens' primary achievement in Panama was in building the infrastructure necessary to complete the canal. He rebuilt the Panama Railway and devised a system for disposing of soil from the excavations by rail. He also built proper housing for canal workers and oversaw extensive sanitation and mosquito-control programmes that eliminated yellow fever and other diseases from the Isthmus. Stevens argued the case against a sea level canal like the French had tried to build. He convinced Theodore Roosevelt of the necessity of a canal built with dams and locks.

An investment was made in eliminating disease from the area, particularly yellow fever and malaria, the causes of which had originally been theorized by Cuban physician/scientist Dr. Carlos Finlay in 1881 who had identified the mosquito as the vector that causes the disease. Finlay's theory and investigative work had recently been confirmed by Dr. Walter Reed while in Cuba with U.S. Army motivation during the Spanish-American War (see Health measures during the construction of the Panama Canal). With the diseases under control, and after significant work on preparing the infrastructure, construction of an elevated canal with locks began in earnest and was finally possible. The Americans also gradually replaced the old French equipment with machinery designed for a larger scale of work (such as the giant hydraulic crushers supplied by the Joshua Hendy Iron Works), to quicken the pace of construction.[6] President Roosevelt had the former French machinery minted into medals for all workers who spent at least two years on the construction to commemorate their contribution to the building of the canal. These medals featured Roosevelt's likeness on the front, the name of the recipient on one side, and the worker's years of service, as well as a picture of the Culebra Cut on the back.[11]

In 1907 Roosevelt appointed George Washington Goethals as Chief Engineer of the Panama Canal. The building of the canal was completed in 1914, two years ahead of the target date of June 1, 1916. The canal was formally opened on August 15, 1914 with the passage of the cargo ship SS Ancon.[12] Coincidentally, this was also the same month that fighting in World War I (the Great War) began in Europe. The advances in hygiene resulted in a relatively low death toll during the American construction; still, 5,609 workers died during this period (1904–1914).[13] This brought the total death toll for the construction of the canal to around 27,500.

A commission was formed in 1922 with a representative from each of the Basin states and one from the Federal Government. The federal representative was Herbert Hoover, then Secretary of Commerce under President Warren Harding. In January 1922, Hoover met with the state governors of Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming to work out an equitable arrangement for apportioning the waters of the Colorado River for their states' use. The resulting Colorado River Compact, signed on November 24, 1922, split the river basin into upper and lower halves with the states within each region deciding how the water would be divided. This agreement, known as the Hoover Compromise, paved the way for the Boulder Dam Project. This huge dam was built to provide irrigation water flow, for flood control, and for hydroelectric-power generation.

...

The contract to build the Boulder Dam was awarded to Six Companies, Inc. on March 11, 1931,[8] a joint venture of Morrison-Knudsen Company of Boise, Idaho; Utah Construction Company of Ogden, Utah; Pacific Bridge Company of Portland, Oregon; Henry J. Kaiser & W. A. Bechtel Company of Oakland, California; MacDonald & Kahn Ltd. of Los Angeles; and the J.F. Shea Company of Portland, Oregon. The chief executive of Six Companies, Frank Crowe, had previously invented many of the techniques used to build the dam.

During the concrete-pouring and curing portion of construction, it was necessary to circulate refrigerated water through tubes in the concrete. This was to remove the heat generated by the chemical reactions that solidify the concrete, since the setting and curing of the concrete was calculated to take about 125 years if cooling was not done. Six Companies, Inc., did much of this work, but it discovered that such a large refrigeration project was beyond its expertise. Hence, the Union Carbide Corporation was contracted to assist with the refrigeration needs.Six Companies, Inc. was contracted to build a new town called Boulder City for workers, but the construction schedule for the dam was accelerated in order to create more jobs in response to the onset of the Great Depression, and the town was not ready when the first dam workers arrived at the site in early 1931. During the first summer of construction, workers and their families were housed in temporary camps like Ragtown while work on the town progressed. Discontent with Ragtown and dangerous working conditions at the dam site led to a strike on August 8, 1931. Six Companies responded by sending in strike-breakers with guns and clubs, and the strike was soon quelled. But the discontent prompted the authorities to speed up the construction of Boulder City, and by the spring of 1932 Ragtown had been deserted.[9] Gambling, drinking alcohol, and prostitution were not permitted in Boulder City during the period of construction. To this day Boulder City is one of only two locations in Nevada not to allow gambling, and the sale of alcohol was illegal until 1969.[10]

While working in the tunnels, many workers suffered from the carbon monoxide generated by the machinery there. The contractors claimed that the sickness was pneumonia and was not their responsibility. When Nevada officials tried to enforce state mining air-quality laws, the contractors took them to court.[11] Officially, only 96 workers died constructing Hoover Dam.[12] Some of the workers sickened and died because of the so-called "pneumonia".[13] Most are uncounted on the official death list.[citation needed] "The Bureau of Reclamations fatality statistics show that 42 deaths were attributed to pneumonia during the construction period, more than any other cause."[14] In January, 1936, the Six Companies made out-of-court settlements, in undisclosed amounts, with fifty gas-suit plaintiffs.[15]

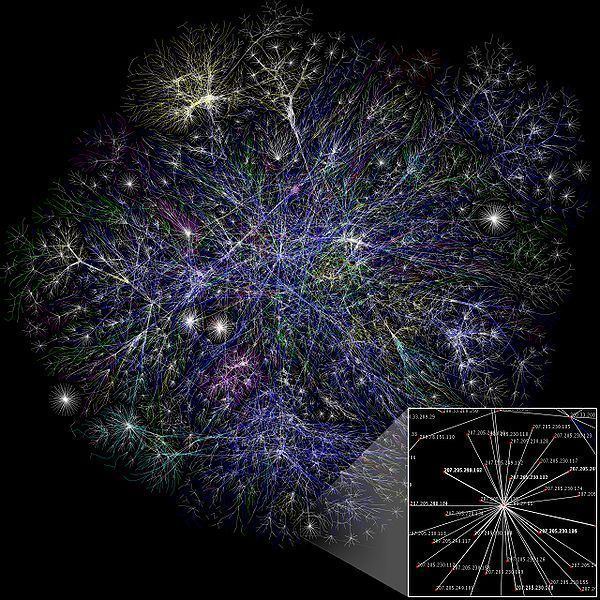

The Internet and the physical backbone infrastructure that makes it possible

The Internet has no centralized governance in either technological implementation or policies for access and usage; each constituent network sets its own standards. Only the overreaching definitions of the two principal name spaces in the Internet, the Internet Protocol address space and the Domain Name System, are directed by a maintainer organization, the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN). The technical underpinning and standardization of the core protocols (IPv4 and IPv6) is an activity of the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF), a non-profit organization of loosely-affiliated international participants that anyone may associate with by contributing technical expertise.

...

During the 1990s, it was estimated that the Internet grew by 100 percent per year, with a brief period of explosive growth in 1996 and 1997.[5] This growth is often attributed to the lack of central administration, which allows organic growth of the network, as well as the non-proprietary open nature of the Internet protocols, which encourages vendor interoperability and prevents any one company from exerting too much control over the network.[6] The estimated population of Internet users is 1.67 billion as of June 30, 2009

Related articles by Zemanta

- Railroad lifts Sierra tunnels for taller trains (sfgate.com)

- High-speed rail plans could soon be back on track for Canada (calgaryherald.com)

- Citizens United Decision: 'A Rejection Of The Common Sense Of The American People' (thinkprogress.org)