"An algorithm must be seen to be believed."

Donald Knuth

How we ended up here

It all began a few days ago with an email from a friend (thanks Denny). I was inspired to dust off my software engineering cap, and review a few choice topics in computer science. What better way to study than to write up a blog post sampling the materials of interest. I accept that in the limited span of blog posts I won't do proper justice to any topic of sufficient depth, that's what books are for. Each post in the series begins with an anchor quote and takes off through the fundamentals of software design theory and practical implementation details with an emphasis on the latter. Much of my sophomoric understanding of computer science comes from iterative practice, reading, and communicating with folks much smarter than myself.

The table of contents for this blog series:

- Intro and Big O

- Object Oriented Programming

- Data Structures: arrays, lists, trees, hash tables

- Algorithms (searches, sorts, maths!)

- Graphs, Networks, and Operating Systems

Algorithms

In short, an algorithm is a recipe.

A formula or set of steps for solving a particular problem. To be an algorithm, a set of rules must be unambiguous and have a clear stopping point. Algorithms can be expressed in any language, from natural languages like English or French to programming languages like FORTRAN

(source)In mathematics and computer science, an algorithm (pronounced /ˈælɡəɹɪðm/ ( listen)) is an effective method expressed as a finite list[1] of well-defined instructions[2] for calculating a function[3]. Algorithms are used for calculation, data processing, and automated reasoning.

(source)

Understanding Strategies beats Memorizing Tactics

Algorithms are well specified techniques for performing an unbounded variety of tasks (good luck learning all algorithms). They are the tactics employed by computer scientists day in and day out, many times without even conscious awareness until further optimization is needed. When working on application specific problems at a high level, it's a distraction to constantly dive into deep operating system and compiler details.

There are broad patterns common to vastly separated problem spaces. These strategies serve as motivations for both design and implementation of algorithms. Divide and conquer and greedy techniques are deployed time and time again within algorithms.

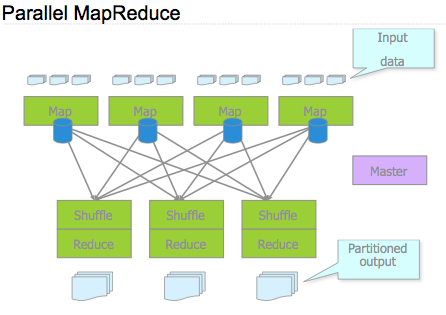

A couple of the most famous divide and conquer techniques are the FFT and MapReduce (slides, web article). The FFT iteratively breaks down the Discrete Fourier Transform into a series of odd and even components until it get's down to a single multiply and add.

I first came across map reduce while reading a set of slides by Jeff Dean, Designs, Lessons and Advice from Building Large Distributed Systems.

I didn't give it much thought at the time, as it appeared to be a good framework for implementing a divide and conquer strategy. A few months later I hit upon MR again while reading through CouchDB's architecture for retrieving documents. It's no surprise sharp folks utilize similar strategies for very different types of problems.

Greedy algorithms make locally optimally decisions, often keeping several potential solutions, and generate a final decision when a forcing function requires an estimate in finite time. One example of a greedy algorithm is an implementation of the Multiple Hypothesis Tracker or MHT. The MHT associates combinations of measurements (factorial growth), calculates likelihood scores, and retains a set number of associations per iteration. At each phase there is always a set of best tracks that it can report out, yet there is a possibility that the global best solution will be pruned during an iteration (heuristics make no guarantees). For understanding the nuances of greedy strategies I defer to the expert, Boss Hog.

Sorting Algorithms

I blame the cruel mistress entropy for the heroic efforts needed to repeatedly sort unorganized data, such is nature. The methods to sort data are as varied as there are ways to visualize it, each algorithm and its implementation is crafted with an artistic touch. If you're looking for a sort to fit your problem's constraints, an excellent starting point is the Wikipedia page which I quote shamelessly below. The gifs from Wikipedia display an animation of each algorithm in action. The gifs cycle through visualizations after a brief pause.

Quicksort sorts by employing a divide and conquer strategy to divide a list into two sub-lists.

The steps are:1)Pick an element, called a pivot, from the list.

2) Reorder the list so that all elements with values less than the pivot come before the pivot, while all elements with values greater than the pivot come after it (equal values can go either way). After this partitioning, the pivot is in its final position. This is called the partition operation. Recursively sort the sub-list of lesser elements and the sub-list of greater elements. The base case of the recursion are lists of size zero or one, which never need to be sorted.

Simple version

In simple pseudocode, the algorithm might be expressed as this: function quicksort(array) var list less, greater if length(array) ≤ 1 return array // an array of zero or one elements is already sorted select and remove a pivot value pivot from array for each x in array if x ≤ pivot then append x to less else append x to greater return concatenate(quicksort(less), pivot, quicksort(greater))

The quicksort on average requires O(n log n) comparisons and worse case O(n^2).

Merge sort

The merge sort implements a divide and conquer strategy. If the size of a sublist is 0 or 1 it's sorted. The merge sort breaks up a list into two sublists of equivalent size. Each sublist is then merged.

The following is a pseudo code example of the algorithm's implementation (source)

function merge_sort(m)

if length(m) ≤ 1

return m

var list left, right, result

var integer middle = length(m) / 2

for each x in m up to middle

add x to left

for each x in m after middle

add x to right

left = merge_sort(left)

right = merge_sort(right)

result = merge(left, right)

return result

function merge(left,right)

var list result

while length(left) > 0 or length(right) > 0

if length(left) > 0 and length(right) > 0

if first(left) ≤ first(right)

append first(left) to result

left = rest(left)

else

append first(right) to result

right = rest(right)

else if length(left) > 0

append first(left) to result

left = rest(left)

else if length(right) > 0

append first(right) to result

right = rest(right)

end while

return result

The merge sort has an average and worst case performance of O(nlogn).

Bubble sort

(source)

(source)

The bubble sort iterates through a collection swapping adjacent elements into a specified order. The process repeats itself until no further elements are swapped. The algorithms average and worst case performance is O(n^2)

Heapsort

The heapsort finds an extreme element (largest or smallest) and places it at one end of the list, continuing until the entire list is sorted. The heap is a binary tree where the root node is larger than any of it's children, key(A) >= key(B). The heap is also a maximally efficient implementation called a priority queue. The average and worst case performance is O(nlogn).

Heapsort begins by building a heap out of the data set, and then removing the largest item and placing it at the end of the partially sorted array. After removing the largest item, it reconstructs the heap, removes the largest remaining item, and places it in the next open position from the end of the partially sorted array. This is repeated until there are no items left in the heap and the sorted array is full. Elementary implementations require two arrays - one to hold the heap and the other to hold the sorted elements.

(source)

It's worth mentioning another heap, the Fibonacci Heap, which I'll come back to in the tomorrow's post on graphs (Dijkstra's search algorithm).

Packing Problems

(source)

The image says it all about packing problems. Your goal is to fit as many N-dimensional structures as possible into the smallest region possible, and the maximum density algorithm wins. If you're really into this type of problem, Dropbox is hiring.

Packing problems are a class of optimization problems in recreational mathematics which involve attempting to pack objects together (often inside a container), as densely as possible. Many of these problems can be related to real life storage and transportation issues. Each packing problem has a dual covering problem, which asks how many of the same objects are required to completely cover every region of the container, where objects are allowed to overlap.

In a packing problem, you are given:

'containers' (usually a single two- or three-dimensional convex region, or an infinite space)

'goods' (usually a single type of shape), some or all of which must be packed into this container

Usually the packing must be without overlaps between goods and other goods or the container walls. The aim is to find the configuration with the maximal density. In some variants the overlapping (of goods with each other and/or with the boundary of the container) is allowed but should be minimised.

(source)

Cryptographic Hash Functions

Cryptography and Encryption Algorithms (thanks to your_perception for the correction)

MD5 was considered a popular and fairly secure cryptographic hash function in the late 1990s, but is now known to have several predictable vulnerabilities. It converts a variable length input string into a 128bit output. SHA-1 is a more recent standard for secure cryptography but is susceptible to other known vulnerabilities (is nothing sacred).

Additional Notes:

There are a few other areas I'd like to include, but I'll have to return and append them to the post at another time (hopefully this weekend time allowing). For now I'll leave these as placeholders as a reminder to myself.

Linear and Dynamic Programming

Linear Programming

Dynamic Programming (so named partly because Dynamic sounded cool)

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning

(source)

Supervised and Unsupervised learning...

Estimation algorithms: Detection, Tracking, Prediction, ie what I do for a living Discrimination: Classification (Quadratic, PNN) Natural language processing (NLP): machine learning applied to big data sets There's no shame in brute force When there's no time for more elegant algorithms, there's little shame in brute forcing your way to a delivery.